skip to main |

skip to sidebar

. . . and a happy New Year. We'll see you then.

On our way out of Cairo today, we stopped by the Tombs of Mohammad Ali's Family, which we were told by our (not exaggerating at all) fantastic taxi driver, were worth 950 million dollars. Mohammad Ali was the first Ottoman emperor of Egypt, who came to power in 1811. Apparently they kept slaves and had them killed off to be buried with them.

The tombs were of course very ornate, very Ottoman, and very shabby-chic. 15 Egyptian Pounds, the entry price, is just under $3. I liked the look of the place, and the sun was just right to really illuminate the stained-glass windows. But by the time we got there it was well into the afternoon, we hadn't eaten since 8 am, and we were all a little bit worried about catching our flights (two of sweetie's colleagues joined us). I guess all of those reasons collided in reducing the amount of time we spent there to about 10 minutes.

The tombs were of course very ornate, very Ottoman, and very shabby-chic. 15 Egyptian Pounds, the entry price, is just under $3. I liked the look of the place, and the sun was just right to really illuminate the stained-glass windows. But by the time we got there it was well into the afternoon, we hadn't eaten since 8 am, and we were all a little bit worried about catching our flights (two of sweetie's colleagues joined us). I guess all of those reasons collided in reducing the amount of time we spent there to about 10 minutes.

However, those ten minutes were choice. Our taxi-tourguide sang to demonstrate the acoustics, rhapsodized on the non-violent nature of Islam, gave thorough explanations of the interior and who was buried where and what the tombs were made of, etc. He even accused Matthew of not believing him.

I don't remember who, but someone told us recently that we just should not even bother with the Egyptian Museum. I wish I could remember now who said that, since I have bothered with it and can now heartily disagree.

It costs about $9 to get in, which is $9 more than the entrance to the British Museum, but that was ok. The museum had the best collection of Egyptian artifacts I have ever seen. Better than London. Better than Berlin. And I was pleased to finally see some of the statuary that I've had knocking around my brain for a decade now. The trans-gender statue of Akhenaton, for one, but that’s a post for another day.

What impressed me most about the Egyptian Museum is that the experience of it is quite different from other major museums--at least the ones I have visited. When you walk in it is as if you have gone back in time. You leave the contemporary self-obsessed confidence found in most museums. The Egyptian Museum, for lack of a better word, is low-tech. Nothing is guarded by lasers that bounce from ceiling to floor. The exhibits are encased in simple glass and wood. There are no sleekly-designed information placards, just paper, type-written with the most basic descriptions. Instead of accession numbers that tell you where and when a piece was discovered, there are at times old photographs of piles of numbered things, and somewhere in that pile is the object in the case. Huge enlargements of similar excavation photos are propped up against the walls, as if no more elegant presentation were possible or necessary. There was, throughout the museum, enough dust to convince anyone that museums might still house hidden treasures. The lighting was terrible. The jewelry was positively inspirational.

What I liked best was that the museum shop sold postcards and books. Nothing else. No neck-ties printed to look like mummies. No recreations. No erasers or chocolates molded to look like ankhs.

This from M.F.K. Fisher's introduction to Map of Another Town:

Often in the sketch of a portrait, the invisible lines that bridge one stroke of the pencil or brush to another are what really make it live. This is probably true in a word picture too. The myriad undrawn unwritten lines are the ones that hold together what the painter and the writer have tried to set down, their own visions of a thing: a town, one town, this town.

Not everything can be told, nor need it be, just as the artist himself need not and indeed cannot reveal every outline of his vision.

I remember one of my favorite passages of one of the Ramona Quimby books described in great detail how Beatrice, Ramona's older sister, labored over a drawing of a fantasy dinosaur, determined not to over-do it. Often the true difficulty of art is not getting a point across. The difficulty is doing it without doing too much. It is probably one element of genius to give just enough and not over do it.

My husband is ill. Violently. He and the girls are resting right now, and well, you know what I’m doing.

We have tickets to go to Cairo on Monday evening, but if my sweetie’s health doesn’t improve quickly, none of us will go. Tagging along on business trips is just like that.

Still, I have Cairo on my mind, and particularly their ancient treasures. I don’t know anyone who isn’t at least a little bit curious about the pyramids, temples, and other ruins of long-gone dynasties. To young Americans, they are among the most familiar of foreign, exotic things. When I was a kid, my parents had a subscription to National Geographic, but also to their jr. version called World. If my memory serves (it doesn’t), every single issue was devoted to Tutankhamen’s tomb.

National Geographic has a great Egypt page. Very informative for people going there literally or virtually. They have a list of sources for further reading and even a list of their own publications about Egypt going back to 1913.

Interestingly, they didn’t include what I think was one of their most significant issues. From what I’ve been able to put together, the Feb 1982 issue was almost entirely devoted to the foregoing century’s discoveries and excavations in Egypt. That issue isn't listed on the current Egypt page. Maybe the reason they don't reference this issue is that the pyramids depicted on the front cover were digitally manipulated to squash them into the available (narrow) space. The ethics of their alteration of the pyramid’s positioning has prompted quite a bit of discussion. Just do a Google search for "National Geographic 1982 Giza".

I don’t know if the 1982 issue was left off the source list for this reason or for no reason at all. If it was deliberately left out, that would signal that NatGeo agrees that its reliability is in question. But there’s a lot to be said for the “no reason at all” argument. They didn’t say their bibliography was a complete one.

I’ve never really been able to decide where I stand on this issue. Digitally shifting a pyramid to the side is not the same as lying about its entire existence, or putting it into the mountains of China. The pyramids are where they belong even if they aren’t exactly there. But National Geographic is a respected source of both excellent scholarship and excellent photography. If they are to be regarded as the standard-bearers for the crossover between art-photography and scholarship, suddenly even a slight "reinterpretation" of where a pyramid actually is really undercuts their reputation.

I was looking through my photos today, looking for any picture that I might have taken of some art somewhere in the last two years. I was looking for something from Lebanon. But I found this:

What you see there are two painted clowns bookended by three of my blood relations. While we were avoiding the summer's war, I was fortunate enough to go apple picking on one very fine day in September. These clowns were part of the gig.

What you see there are two painted clowns bookended by three of my blood relations. While we were avoiding the summer's war, I was fortunate enough to go apple picking on one very fine day in September. These clowns were part of the gig.

I had entirely forgotten that they were there until I saw the picture. Now, I'm completely convinced that they were in fact there, even though I really have no recollection of it. And the more I consider it, the more I am sure that I actually do have a vague memory of those silly cut-out clowns.

That's the power of a photograph. It gave me a memory that even my own brain did not. I'm not saying this is art, just commenting on one of the many assumptions that each of us bring to a photographic image.

I just read the NYT’ rather ironic, (and I conclude) unfavorable review of The Architecture Of Happiness by Alain de Botton, which contained this little, priceless gem:

As John Ruskin observed, we don’t want our buildings merely to shelter us; we also want them to speak to us. But of what? De Botton has an answer. Great buildings, he says, “speak of visions of happiness.”

Up until the precise moment, I really did believe that beauty was the most subjective of all things, but de Botton has shown me my error. But really, could happiness become the new beauty? All chiding aside, I’d like to read that book. I’ve added it to my list of books to test drive at the library just as soon as I live in a country that has one to patronize.

Sorry to be so self-referential, but I also promised in the very comment thread that inspired yesterday’s musings to tell you all what I think about Jasper John’s White Flag. So, here’s a bit about that.

Most of what I know about Jasper Johns actually is stuff that I came across entirely unintentionally. He was one of Warhol’s contemporaries, and because of that, a lot of books about one mention the other. They were both significant, distinct forces. Anyway, Johns was really young when he became really famous and that somehow seems to have worked out. Warhol, by all accounts was envious of Johns, and his early work reflects that—some flattery-in-the-form-of-imitation, if you will. Johns’ paintings have been sold for more money than those of any other painter alive today. The most expensive one? 80 million. And they say the arts don’t pay.

Anyway, the cool things about White Flag are numerous. Most of these start with the flag itself and all the messages that they bring with them. Move it into the art scene of the mid 1950s, with its cares and concerns and those messages multiply.

Flags. They’re like pictographs, really. Any *real* American can tell you that there are 13 stripes for the 13 colonies that broke away from Britain, 50 stars represent each of the current states. We also have so much associated with this flag—seeing it draped over the coffins of dead soldiers and presidents, flown at half-mast, waved proudly every July 4th, Memorial and Veteran’s Day. We watched it be burned in acts of civil disobedience and International protest. We’ve seen it printed in the kitschiest fashion on t-shirts and coffee mugs. We even have songs about our flag.

So the US flag is a loaded symbol, particularly for Americans but (risking arrogance yet knowing I’m right) for every one else too. Merge that flag with white and suddenly you have all the connotations of surrender. I wonder if he was going for that or if he was instead exploring the design of the flag, maybe in an effort to assert that his painting isn’t a flag at all. It's a painting.

This comment was left by Suz about five months ago when I featured Jasper John's White Flag in this post:

i thought it was interesting that johns was described as a neo-dadaist as well as a pop artist. that made me think of a question i'v been meaning to ask you. i was having an art discussion with my roommate who is a tattoo artist/painter, in which he commented "as an artist, i think that stuff like duchamp's 'fountain' is the biggest insult to the work i do" i'm rather curious about your thoughts on this- might make a good upcoming post, maybe?

Thanks for the question. I hope I can provide a satisfactory response, even though the closest I have ever come to "body art" are those face-painting booths at carnivals.

My first thought is that, tattoo artists are very likely quite good at getting a butterfly to look like a butterfly, or an anchor to look like an anchor. Because of this your roommate probably sees craftsmanship as an integral part of what it is to create art. Tattoos, frankly, have to meet certain visual expectations. No one wants bumbling imperfection burned into their flesh. And having painted faces a time or two myself, I recognize that flesh is not the easiest foundation for such work.

In addition to good technique, I'd imagine that a tattoo artist also needs at least a little artistic feeling. Probably, there are customers out there who are not satisfied with the same old tattoo that everyone else already has. Creativity, improvisation, even thoughtful re-interpretation are skills that such an artist would likely do well to have in his arsenal. Otherwise, people could just get branded and have the whole thing done in one very painful go.

In the case of the tattoo-artist-friend-roommate, my guess is that he sees Duchamp's work as an insult to the requisite technique of his medium--as an insult to anyone who has acquired that skill through hard work, practice, maybe a few black-eyes if it went wrong . . .

Fountain can be seen as an insult to certain definitions of craftsmanship, but I don't see it as an insult to craftsmanship itself. Duchamp's interest was in searching out the fringes, the gray area between art and not art. His Fountain was less an assertion than this question: "can it still be art, even though there is no reason for it be except that I say it is?" Ever since, that question has driven art and artists and has become one of art's most productive inquiries of the 20th century.

Rather than insulting fields that require high levels of skill and technique, I believe Fountain simply differentiates itself from them. Art can be found in exquisite craftsmanship, but after Fountain, it can be found elsewhere too.

This is another installment in an ongoing series.

Back when I first came across Art History as a discipline—a major study option at the university—I imagined it would be something like history from the perspective of art. I thought of the world civilization courses that I’d had in the past and envisioned a place where art would play a bigger role in essentially the same discussions of the past.

Oh, no. No, no, no.

Art History is the history of art. Certainly, one could use art to tell the history of a group, people, culture, or slice of time. I think it would work quite well, too. But after all the studying, reading, learning, researching, etc. that I have engaged in over the last decade-and-then-some, I find that I still could tell you very little about the historic events that surrounded and in some cases created the art and theory about which I (immodestly) know buckets.

This, I suppose should be the first of Art History’s Problematic Situations. It causes a foundation-level tension between historiography and the far more limited task of charting art’s history. And though Art History is at times undermined and crippled by its own issues, history proper is nothing if not worse.

Sadly, I don't have very many art books for children, but I do have Can You Find It, Too? (Thanks Bonnie!), which showcases some of the amazing art at the Metropolitan Museum. It works like Where's Waldo, except that it isn't Waldo and the visual style of each scene differs by centuries, continents, and media. I love the variety in this book, and the things that you search for are surprising and perfect for little kids. In one image (probably 1920s) of the seashore, packed with families, children, and dogs, you get to find among many other things, the one and only dog on a leash. In another picture from the 1700s of a busy Chinese city there are very few children, but only two women. An ancient Egyptian Hieroglyph has only one falcon, but 22 eyes and 30 feet, and your job is to find them all.

Sadly, I don't have very many art books for children, but I do have Can You Find It, Too? (Thanks Bonnie!), which showcases some of the amazing art at the Metropolitan Museum. It works like Where's Waldo, except that it isn't Waldo and the visual style of each scene differs by centuries, continents, and media. I love the variety in this book, and the things that you search for are surprising and perfect for little kids. In one image (probably 1920s) of the seashore, packed with families, children, and dogs, you get to find among many other things, the one and only dog on a leash. In another picture from the 1700s of a busy Chinese city there are very few children, but only two women. An ancient Egyptian Hieroglyph has only one falcon, but 22 eyes and 30 feet, and your job is to find them all.

If you read the reviews at Amazon’s website, you'll see that there are some who think a few images are too violent, and they are probably right. Beheadings aren't really for little tykes. But as a mom who unconcernedly handed this book to my children, who am I to judge?

We will now depart from Impart Art's normal features to present this report on festive goings-on

Tuesday night the girls, in proper German fashion, each put a boot outside our front door. There was an old legend, I told them, that Santa had been sent on an errand to leave candy at the homes of all the good girls and boys. To let Santa know where to find you, all you have to do is put your boot out for him. So, we did. After they were in bed, I filled each boot (a rather tight squeeze) with the things you see the girls enjoying below:

I expected that the girls would forget overnight what they’d done with their boots, but they didn’t. Before enjoying their treats though, we delivered two paper Christmas trees with candy taped on them to our neighbors. We tried very hard to be silent and sneaky in the stairwell.

This year, the smallest chocolate santas were the ones made by the Kinderschokolade people, which is why they are white inside. I had to get small ones because tiny kids have tiny boots. Yes, Dandelion has her chocolate santa and Star's. Star was bored with candy by the time I got this picture. What you can't see is how Dandelion struggled to hold both santas, her marshmallow rope, and eat gummy bears out of a little sack all at once.

Go ahead, click it, make it big enough to read.

And, because I'm aching to get in trouble for something, here's a speech Watterson gave that I most definately don't have permission to republish. I nevertheless believe that it is among the most worthwhile reading a person could do. I dare you to read it all, and if you can manage it, leave me a comment with your favorite line in it, or if you are a compelte weirdo, your least favorite line.

****

Speech by Bill Watterson

Kenyon College, Gambier Ohio, to the 1990 graduating class.

SOME THOUGHTS ON THE REAL WORLD BY ONE WHO GLIMPSED IT AND FLED

Bill Watterson

Kenyon College Commencement

May 20, 1990

I have a recurring dream about Kenyon. In it, I'm walking to the post office on the way to my first class at the start of the school year. Suddenly it occurs to me that I don't have my schedule memorized, and I'm not sure which classes I'm taking, or where exactly I'm supposed to be going.

As I walk up the steps to the postoffice, I realize I don't have my box key, and in fact, I can't remember what my box number is. I'm certain that everyone I know has written me a letter, but I can't get them. I get more flustered and annoyed by the minute. I head back to Middle Path, racking my brains and asking myself, "How many more years until I graduate? ...Wait, didn't I graduate already?? How old AM I?" Then I wake up.

Experience is food for the brain. And four years at Kenyon is a rich meal. I suppose it should be no surprise that your brains will probably burp up Kenyon for a long time. And I think the reason I keep having the dream is because its central image is a metaphor for a good part of life: that is, not knowing where you're going or what you're doing.

I graduated exactly ten years ago. That doesn't give me a great deal of experience to speak from, but I'm emboldened by the fact that I can't remember a bit of MY commencement, and I trust that in half an hour, you won't remember of yours either.

In the middle of my sophomore year at Kenyon, I decided to paint a copy of Michelangelo's "Creation of Adam" from the Sistine Chapel on the ceiling of my dorm room. By standing on a chair, I could reach the ceiling, and I taped off a section, made a grid, and started to copy the picture from my art history book.

Working with your arm over your head is hard work, so a few of my more ingenious friends rigged up a scaffold for me by stacking two chairs on my bed, and laying the table from the hall lounge across the chairs and over to the top of my closet. By climbing up onto my bed and up the chairs, I could hoist myself onto the table, and lie in relative comfort two feet under my painting. My roommate would then hand up my paints, and I could work for several hours at a stretch.

The picture took me months to do, and in fact, I didn't finish the work until very near the end of the school year. I wasn't much of a painter then, but what the work lacked in color sense and technical flourish, it gained in the incongruity of having a High Renaissance masterpiece in a college dorm that had the unmistakable odor of old beer cans and older laundry.

The painting lent an air of cosmic grandeur to my room, and it seemed to put life into a larger perspective. Those boring, flowery English poets didn't seem quite so important, when right above my head God was transmitting the spark of life to man.

My friends and I liked the finished painting so much in fact, that we decided I should ask permission to do it. As you might expect, the housing director was curious to know why I wanted to paint this elaborate picture on my ceiling a few weeks before school let out. Well, you don't get to be a sophomore at Kenyon without learning how to fabricate ideas you never had, but I guess it was obvious that my idea was being proposed retroactively. It ended up that I was allowed to paint the picture, so long as I painted over it and returned the ceiling to normal at the end of the year. And that's what I did.

Despite the futility of the whole episode, my fondest memories of college are times like these, where things were done out of some inexplicable inner imperative, rather than because the work was demanded. Clearly, I never spent as much time or work on any authorized art project, or any poli sci paper, as I spent on this one act of vandalism.

It's surprising how hard we'll work when the work is done just for ourselves. And with all due respect to John Stuart Mill, maybe utilitarianism is overrated. If I've learned one thing from being a cartoonist, it's how important playing is to creativity and happiness. My job is essentially to come up with 365 ideas a year.

If you ever want to find out just how uninteresting you really are, get a job where the quality and frequency of your thoughts determine your livelihood. I've found that the only way I can keep writing every day, year after year, is to let my mind wander into new territories. To do that, I've had to cultivate a kind of mental playfulness.

We're not really taught how to recreate constructively. We need to do more than find diversions; we need to restore and expand ourselves. Our idea of relaxing is all too often to plop down in front of the television set and let its pandering idiocy liquefy our brains. Shutting off the thought process is not rejuvenating; the mind is like a car battery-it recharges by running.

You may be surprised to find how quickly daily routine and the demands of "just getting by: absorb your waking hours. You may be surprised to find how quickly you start to see your politics and religion become matters of habit rather than thought and inquiry. You may be surprised to find how quickly you start to see your life in terms of other people's expectations rather than issues. You may be surprised to find out how quickly reading a good book sounds like a luxury.

At school, new ideas are thrust at you every day. Out in the world, you'll have to find the inner motivation to search for new ideas on your own. With any luck at all, you'll never need to take an idea and squeeze a punchline out of it, but as bright, creative people, you'll be called upon to generate ideas and solutions all your lives. Letting your mind play is the best way to solve problems.

For me, it's been liberating to put myself in the mind of a fictitious six year-old each day, and rediscover my own curiosity. I've been amazed at how one ideas leads to others if I allow my mind to play and wander. I know a lot about dinosaurs now, and the information has helped me out of quite a few deadlines.

A playful mind is inquisitive, and learning is fun. If you indulge your natural curiosity and retain a sense of fun in new experience, I think you'll find it functions as a sort of shock absorber for the bumpy road ahead.

So, what's it like in the real world? Well, the food is better, but beyond that, I don't recommend it.

I don't look back on my first few years out of school with much affection, and if I could have talked to you six months ago, I'd have encouraged you all to flunk some classes and postpone this moment as long as possible. But now it's too late.

Unfortunately, that was all the advice I really had. When I was sitting where you are, I was one of the lucky few who had a cushy job waiting for me. I'd drawn political cartoons for the Collegian for four years, and the Cincinnati Post had hired me as an editorial cartoonist. All my friends were either dreading the infamous first year of law school, or despondent about their chances of convincing anyone that a history degree had any real application outside of academia.

Boy, was I smug.

As it turned out, my editor instantly regretted his decision to hire me. By the end of the summer, I'd been given notice; by the beginning of winter, I was in an unemployment line; and by the end of my first year away from Kenyon, I was broke and living with my parents again.

You can imagine how upset my dad was when he learned that Kenyon doesn't give refunds.

Watching my career explode on the lauchpad caused some soul searching. I eventually admitted that I didn't have what it takes to be a good political cartoonist, that is, an interest in politics, and I returned to my firs love, comic strips.

For years I got nothing but rejection letters, and I was forced to accept a real job.

A REAL job is a job you hate. I designed car ads and grocery ads in the windowless basement of a convenience store, and I hated every single minute of the 4-1/2 million minutes I worked there. My fellow prisoners at work were basically concerned about how to punch the time clock at the perfect second where they would earn another 20 cents without doing any work for it.

It was incredible: after every break, the entire staff would stand around in the garage where the time clock was, and wait for that last click. And after my used car needed the head gasket replaced twice, I waited in the garage too.

It's funny how at Kenyon, you take for granted that the people around you think about more than the last episode of Dynasty. I guess that's what it means to be in an ivory tower.

Anyway, after a few months at this job, I was starved for some life of the mind that, during my lunch break, I used to read those poli sci books that I'd somehow never quite finished when I was here. Some of those books were actually kind of interesting. It was a rude shock to see just how empty and robotic life can be when you don't care about what you're doing, and the only reason you're there is to pay the bills.

Thoreau said,

"the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation."

That's one of those dumb cocktail quotations that will strike fear in your heart as you get older. Actually, I was leading a life of loud desperation.

When it seemed I would be writing about "Midnite Madness Sale-abrations" for the rest of my life, a friend used to console me that cream always rises to the top. I used to think, so do people who throw themselves into the sea.

I tell you all this because it's worth recognizing that there is no such thing as an overnight success. You will do well to cultivate the resources in yourself that bring you happiness outside of success or failure. The truth is, most of us discover where we are headed when we arrive. At that time, we turn around and say, yes, this is obviously where I was going all along. It's a good idea to try to enjoy the scenery on the detours, because you'll probably take a few.

I still haven't drawn the strip as long as it took me to get the job. To endure five years of rejection to get a job requires either a faith in oneself that borders on delusion, or a love of the work. I loved the work.

Drawing comic strips for five years without pay drove home the point that the fun of cartooning wasn't in the money; it was in the work. This turned out to be an important realization when my break finally came.

Like many people, I found that what I was chasing wasn't what I caught. I've wanted to be a cartoonist since I was old enough to read cartoons, and I never really thought about cartoons as being a business. It never occurred to me that a comic strip I created would be at the mercy of a bloodsucking corporate parasite called a syndicate, and that I'd be faced with countless ethical decisions masquerading as simple business decisions.

To make a business decision, you don't need much philosophy; all you need is greed, and maybe a little knowledge of how the game works.

As my comic strip became popular, the pressure to capitalize on that popularity increased to the point where I was spending almost as much time screaming at executives as drawing. Cartoon merchandising is a $12 billion dollar a year industry and the syndicate understandably wanted a piece of that pie. But the more I though about what they wanted to do with my creation, the more inconsistent it seemed with the reasons I draw cartoons.

Selling out is usually more a matter of buying in. Sell out, and you're really buying into someone else's system of values, rules and rewards.

The so-called "opportunity" I faced would have meant giving up my individual voice for that of a money-grubbing corporation. It would have meant my purpose in writing was to sell things, not say things. My pride in craft would be sacrificed to the efficiency of mass production and the work of assistants. Authorship would become committee decision. Creativity would become work for pay. Art would turn into commerce. In short, money was supposed to supply all the meaning I'd need.

What the syndicate wanted to do, in other words, was turn my comic strip into everything calculated, empty and robotic that I hated about my old job. They would turn my characters into television hucksters and T-shirt sloganeers and deprive me of characters that actually expressed my own thoughts.

On those terms, I found the offer easy to refuse. Unfortunately, the syndicate also found my refusal easy to refuse, and we've been fighting for over three years now. Such is American business, I guess, where the desire for obscene profit mutes any discussion of conscience.

You will find your own ethical dilemmas in all parts of your lives, both personal and professional. We all have different desires and needs, but if we don't discover what we want from ourselves and what we stand for, we will live passively and unfulfilled. Sooner or later, we are all asked to compromise ourselves and the things we care about. We define ourselves by our actions. With each decision, we tell ourselves and the world who we are. Think about what you want out of this life, and recognize that there are many kinds of success.

Many of you will be going on to law school, business school, medical school, or other graduate work, and you can expect the kind of starting salary that, with luck, will allow you to pay off your own tuition debts within your own lifetime.

But having an enviable career is one thing, and being a happy person is another.

Creating a life that reflects your values and satisfies your soul is a rare achievement. In a culture that relentlessly promotes avarice and excess as the good life, a person happy doing his own work is usually considered an eccentric, if not a subversive. Ambition is only understood if it's to rise to the top of some imaginary ladder of success. Someone who takes an undemanding job because it affords him the time to pursue other interests and activities is considered a flake. A person who abandons a career in order to stay home and raise children is considered not to be living up to his potential-as if a job title and salary are the sole measure of human worth.

You'll be told in a hundred ways, some subtle and some not, to keep climbing, and never be satisfied with where you are, who you are, and what you're doing. There are a million ways to sell yourself out, and I guarantee you'll hear about them.

To invent your own life's meaning is not easy, but it's still allowed, and I think you'll be happier for the trouble.

Reading those turgid philosophers here in these remote stone buildings may not get you a job, but if those books have forced you to ask yourself questions about what makes life truthful, purposeful, meaningful, and redeeming, you have the Swiss Army Knife of mental tools, and it's going to come in handy all the time.

I think you'll find that Kenyon touched a deep part of you. These have been formative years. Chances are, at least one of your roommates has taught you everything ugly about human nature you ever wanted to know.

With luck, you've also had a class that transmitted a spark of insight or interest you'd never had before. Cultivate that interest, and you may find a deeper meaning in your life that feeds your soul and spirit. Your preparation for the real world is not in the answers you've learned, but in the questions you've learned how to ask yourself.

Graduating from Kenyon, I suspect you'll find yourselves quite well prepared indeed.

I wish you all fulfillment and happiness. Congratulations on your achievement.

Bill Watterson

In two months and 10 days, Lebanon will certainly commemorate the death of Rafik Hariri, whose assassination marked the beginning of the turmoil that has gripped Lebanon for the past two years. From the beginning, it was assumed that Syria was to blame for Hariri’s death. One month after the assassination, hundreds of thousands of Lebanese descended on Beirut’s central district to express their anger at the Syrian-backed leadership of their country. They called for the immediate withdraw of Syria from Lebanon. With the help of the international community acting through the United Nations, Syrian troops were removed from the country, but their influence lingered. If the UN investigative body is to be believed, Syria’s influence in the country has been evidenced by a steady trail of assassinations spread over the past two years.

Why then, is the current political climate pro-Syrian? Why are there hundreds of thousands of Lebanese demonstrating in favor of the very leadership that was blamed for Hariri’s death? Well, lets not forget the summer’s war. Although the United States was quick to express concern for Lebanon when Syria was seen as the culprit, they turned a blind eye when Israel came knocking. The UN peacekeepers at the boarder did not prevent or intervene in the hostilities. There they were, doing nothing.

So Hezbollah was the closest thing to a defender that the south had. There was every appearance at the beginning that Israel was going to do to Lebanon what it had been doing to Gaza for weeks—strangle, starve, and suffocate. And it didn’t happen. Israel essentially gave up the fight. No wonder Hezbollah has claimed a divine victory. No wonder so many Lebanese see it that way.

But there are many others who don’t. Every day, I see people in number heading downtown to continue the ongoing protests intended to bring down the western-leaning government. And every day, as I walk or drive through the city, I see Lebanese flags hanging from balconies—the sign of those who despite the war are still against Syrian interference.

Recently, the New York Times reviewed an art exhibit here in Lebanon, aimed at identifying what it is to be Lebanese and what their country ought to become. The author observed, “all of the main . . . confessional communities (Christian, Sunni, Shiite, Druse), want a Lebanon united by their definition of what Lebanon should be.” Each sect believes they are the real Lebanon.

The article made some valuable observations on contemporary divisions within the country, and for that it was worth a read. But I’m not sure the art at the center of it would be worth looking at. There were only a few, bad photos of the show and the descriptions given by the author were lifeless.

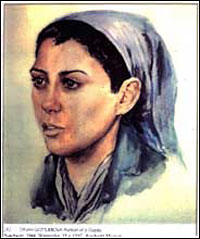

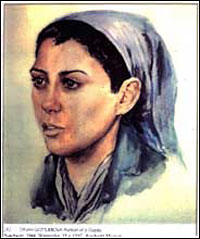

I’ve just listened to an interesting NPR story about a prisoner at Auschwitz who was assigned to paint watercolor portraits of her fellow prisoners because (according to the Nazi commander there) photographs simply weren’t satisfactorily capturing the degenerate qualities of the gypsies.

Here is one such image. It was painted by Dina Gottliebova Babbitt, who is now 83 years old and wants ownership of her work. The Auschwitz museum claims ownership of anything that serves as evidence of the place's history.

Here is one such image. It was painted by Dina Gottliebova Babbitt, who is now 83 years old and wants ownership of her work. The Auschwitz museum claims ownership of anything that serves as evidence of the place's history.

NPR’s story wasn’t about the merits of photos vs. paintings, but I can't help thinking about that. I’ve been wondering if artists choose to do what they do. My guess is that it is rarely a case where a person weighed the options and chose one medium over the other. More often than not, people go with the medium they happened to learn before they really thought about being an “artist”, be it drawing, photography, or even the new technology-media. There's usually a predisposition. But here, it was a clear choice, and a completely backward seeming one.

Nobody today, except in closed court rooms, would turn to a painting for evidence. Photographs, which make the most credible appeal to reality of any of art’s expressive forms, were thought “not real enough” in this case. It seems like proof enough to me that what the Nazi’s saw in these lesser races was a projection of their inner horrors. Why else would a subjective art, like painting, be seen as more accurate than a documentary photography?

I took a class about the arts associated with Zen and Tao shortly before we moved to Beirut. I was fascinated by the subject matter, delighted by the application of these philosophies/religions to the arts, culture, and even aspects of daily living. The harmony among these seemingly divided pursuits appealed to my sense of universalism. That art, belief, and life are all part of the same big picture is something that I have always felt anyway.

Among the arts that Zen influences is the tea ceremony. There are whole books, some of them ancient, about how to properly prepare, present, and drink tea. They describe in detail the correct proportion and appointment of the room, the manner of the guests, their optimal mode of dress, arrival, and conversation.

Tea continues to be an art in Japan, and a ritual in Britain. It was neither in my childhood home. My mother drank tea only when she was ill, and encouraged all of us to do the same. She drank an infusion called ‘rose-hip’ which still makes me think of head colds and flu bugs. I have no memory of ever taking her up on her offer, but she still swears by it.

Later, when I was an adult and went a-traveling, I discovered that with enough sugar anything tastes great, and a hot cup of anything takes the edge off a cold day. I began experimenting with my favorite drinks and found that flat soda is down right divine hot. Root Beer becomes sassafras tea. Sprite becomes a delicate lemony delight.

I don’t care for sugar as much as I used to, which I guess means I’m getting old. It actually makes my mouth ache. Plus, I never have flat soda around like I did when I was single. The stuff gets consumed before it has a chance to fizzle out. When I went to London last month I had the best cup of peppermint tea that I have ever had. I had it without sugar because there was no sugar on my table. And I admit, I’m hooked. Every morning since I got back to Beirut I’ve had a cup of peppermint tea. A box of individually wrapped bags had been lurking in our cabinet since the beginning of 2005.

Some of you know that I was learning French this summer, and lets just say I’m still an absolute beginner. I can’t even say “I’m learning French” in French. Today that came back to bite me when, at the grocery store I bought green tea with peppermint instead of peppermint all by itself because I didn’t bother to realize that vert means green.

It smells fantastic.

I can not find even one authoritative source that indicates its status within the LDS church’s dietary guidelines. I’ve done all the research I can, and I have come to what I think is a very safe conclusion about it. Does anyone out there have access to anything authoritative about this?

Consider this:

When asked to provide details about his life to a curator, the painter Balthus sent the following telegram in reply: "No biographical details. Begin: Balthus is a painter of whom nothing is known. Now let us look at the pictures. Regards. B." Balthus was rebelling against the modern fondness for viewing an artist's output through the prism of his public image. He worried that once an artist's personal life was known, his work would be seen only as a means of diagnosing the artist's psychological shortcomings and not as an end in itself. (found here)

So, do Vincent's letters to Theo make Starry Night a better picture? Did Warhol's attention-craving-madness make his silkscreenes art? Would it have mattered if Jackson Pollock had instead been Jackie? What if Picasso hadn't been a womanizer?

Pictures rarely, if ever, stand alone. There is always a context, a background, an origin. All too often, a person's lifestyle choices are seen as an integral part of the images they make. But what if everything we (think we) know is wrong? Do we read art one way for a suicide, and another way for death by natural causes? Do we read the art by men one way and women another? What exactly are our foregon conclusions about a life that are transposed onto the image we see?

The tombs were of course very ornate, very Ottoman, and very shabby-chic. 15 Egyptian Pounds, the entry price, is just under $3. I liked the look of the place, and the sun was just right to really illuminate the stained-glass windows. But by the time we got there it was well into the afternoon, we hadn't eaten since 8 am, and we were all a little bit worried about catching our flights (two of sweetie's colleagues joined us). I guess all of those reasons collided in reducing the amount of time we spent there to about 10 minutes.

The tombs were of course very ornate, very Ottoman, and very shabby-chic. 15 Egyptian Pounds, the entry price, is just under $3. I liked the look of the place, and the sun was just right to really illuminate the stained-glass windows. But by the time we got there it was well into the afternoon, we hadn't eaten since 8 am, and we were all a little bit worried about catching our flights (two of sweetie's colleagues joined us). I guess all of those reasons collided in reducing the amount of time we spent there to about 10 minutes. What you see there are two painted clowns bookended by three of my blood relations. While we were avoiding the summer's war, I was fortunate enough to go apple picking on one very fine day in September. These clowns were part of the gig.

What you see there are two painted clowns bookended by three of my blood relations. While we were avoiding the summer's war, I was fortunate enough to go apple picking on one very fine day in September. These clowns were part of the gig. Sadly, I don't have very many art books for children, but I do have Can You Find It, Too? (Thanks Bonnie!), which showcases some of the amazing art at the Metropolitan Museum. It works like Where's Waldo, except that it isn't Waldo and the visual style of each scene differs by centuries, continents, and media. I love the variety in this book, and the things that you search for are surprising and perfect for little kids. In one image (probably 1920s) of the seashore, packed with families, children, and dogs, you get to find among many other things, the one and only dog on a leash. In another picture from the 1700s of a busy Chinese city there are very few children, but only two women. An ancient Egyptian Hieroglyph has only one falcon, but 22 eyes and 30 feet, and your job is to find them all.

Sadly, I don't have very many art books for children, but I do have Can You Find It, Too? (Thanks Bonnie!), which showcases some of the amazing art at the Metropolitan Museum. It works like Where's Waldo, except that it isn't Waldo and the visual style of each scene differs by centuries, continents, and media. I love the variety in this book, and the things that you search for are surprising and perfect for little kids. In one image (probably 1920s) of the seashore, packed with families, children, and dogs, you get to find among many other things, the one and only dog on a leash. In another picture from the 1700s of a busy Chinese city there are very few children, but only two women. An ancient Egyptian Hieroglyph has only one falcon, but 22 eyes and 30 feet, and your job is to find them all.

Here is one such image. It was painted by Dina Gottliebova Babbitt, who is now 83 years old and wants ownership of her work. The Auschwitz museum claims ownership of anything that serves as evidence of the place's history.

Here is one such image. It was painted by Dina Gottliebova Babbitt, who is now 83 years old and wants ownership of her work. The Auschwitz museum claims ownership of anything that serves as evidence of the place's history.